Imagine you’ve got this brilliant idea for a video game. It’s vivid in your mind: the world, the characters, the core mechanic that will blow players away. You start telling friends, maybe even some potential collaborators, and you see their eyes glaze over. Or worse, everyone walks away with a different interpretation of what your game actually is. This is precisely where a clear Game Overview & Premise becomes your most potent superpower. It’s not just a document; it’s the Rosetta Stone for your creative vision, ensuring everyone, from the coders to the concept artists to future players, understands the very soul of your game.

Forget the dry, academic treatises on game design. This guide is your no-nonsense playbook for articulating your game's essence, making it easy to understand, exciting to discuss, and rock-solid for development. We're going to dive into how to craft compelling overviews and premises that don't just exist but work for you.

At a Glance: Your Game's Core Defined

- Game Overview & Premise distills your game’s core identity, story, and intended experience.

- It serves as the foundational communication tool for everyone involved, from concept to launch.

- Game Design Documents (GDDs) are living blueprints, adaptable to different audiences and project stages.

- Game Plot Summaries are critical for aligning narrative, identifying issues, and engaging your development team early.

- Start simple, iterate often, and always prioritize clarity and player experience.

- Your goal: Create a shared vision that fuels development and captivates future players.

Why Your Game's Core Narrative Needs a North Star

Every blockbuster movie, every epic novel, every genre-defining game begins with a clear, compelling idea. Without a robust Game Overview & Premise, your project is like a ship without a rudder – it might drift, but it won’t reach its intended destination. This foundational work isn't just about documentation; it’s about clarity, alignment, and preventing costly missteps down the line.

Think of it as your game's elevator pitch, business plan, and story bible all rolled into one, tailored for different needs. It ensures that when your artist draws a character, they're drawing your character. When your engineer designs a system, it supports your core gameplay loop. It’s the constant reference point that keeps everyone pulling in the same direction, saving countless hours, dollars, and headaches.

The Game Design Document (GDD): Your Project's Living Blueprint

At the heart of defining your game's overview and premise often lies the Game Design Document (GDD). In its essence, a GDD is a detailed guide that articulates what your game is and how it will function. It's a critical tool for communicating core themes, styles, features, mechanics, and ideas across your entire team, to potential publishers, stakeholders, and even yourself for project tracking.

While some might argue that traditional, monolithic GDDs are relics of a bygone era, the spirit of the GDD—the act of documenting and communicating design ideas—is more vital than ever. It's not about creating an immutable, encyclopedic tome that nobody reads, but rather a flexible, adaptable tool that evolves with your game. For any project involving more than just you, or even for solo developers needing to crystallize their thoughts, a GDD in some form is invaluable. It forces you to clarify how your game will work, transforming vague notions into concrete plans.

Tailoring Your Overview: Different GDDs for Different Audiences

There's no one-size-fits-all GDD. The best GDD is one that serves its specific purpose and audience. Just like you wouldn't use a highly technical design document to pitch to an investor, you wouldn't use a marketing-focused one to detail enemy AI behaviors. Understanding these distinctions is key to effective communication.

1. The One-Page Wonder: High-Level Clarity

Sometimes called a "design brief" or "game concept document," this is the leanest, most agile form of a GDD. It's perfect for quickly conveying the game's essence and getting initial buy-in. It prioritizes conciseness to ensure rapid comprehension.

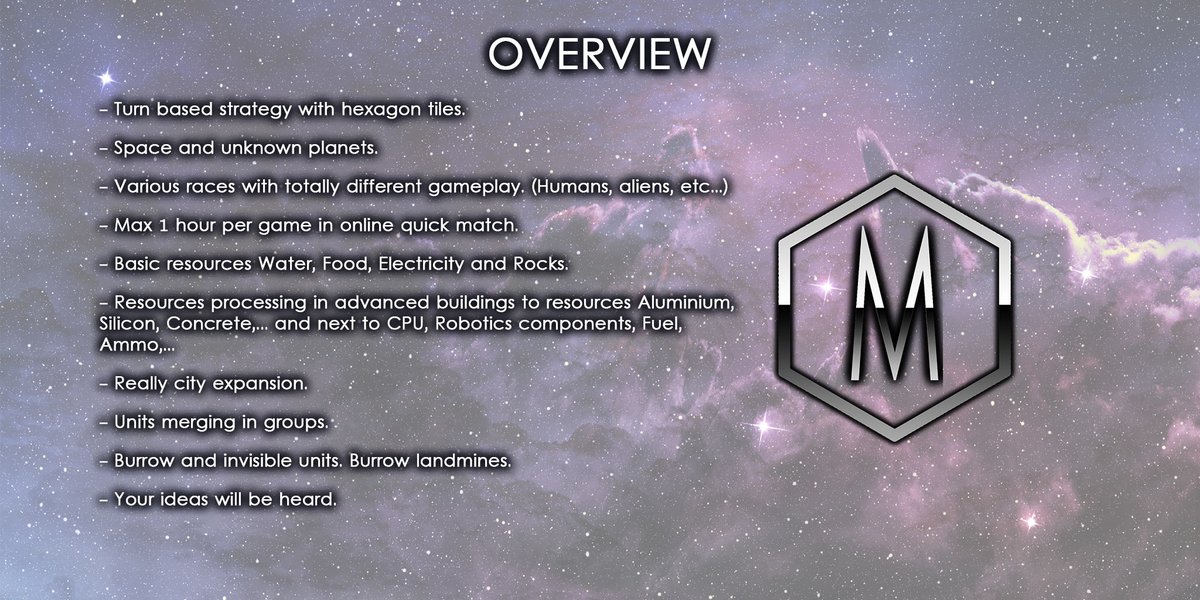

- What it includes: Core concept (your elevator pitch), design pillars (the 2-3 unique selling points), main features & mechanics, target platform & audience, basic story, visual style, and similar games/genres (comps).

- When to use it: Early brainstorming, quick pitches, internal team alignment on the core idea. It's a fantastic starting point for any project.

- Pro Tip: Think visually. Stone Librande's approach to the one-page GDD emphasizes visual communication, using flowcharts for UI or maps for levels, making each page standalone and instantly graspable.

2. The Pitch Perfect: Marketing & Business Focus

When you're seeking funding or a publishing deal, your GDD needs to speak the language of business. This isn't just about your game; it's about its viability as a commercial product. - What it includes: Target platform & audience, monetization strategy & price point, social engagement & wishlist potential, thorough competition analysis, unique selling points (USPs), new experiences or technologies employed, previous game performance (if applicable), detailed cost breakdown, future opportunities (DLC, sequels), and a comprehensive market analysis.

- When to use it: Pitching to investors, publishers, or internal stakeholders who need to understand the financial and market potential.

- Key takeaway: This document functions as a business proposal, translating your creative vision into a compelling commercial opportunity.

3. The Aesthetic Deep Dive: Design & Style GDD

This type of GDD refines and shares the game's overall look, feel, and narrative backbone. It ensures artistic consistency and emotional resonance. - What it includes: Detailed character descriptions (with concept art), comprehensive story outline, deep lore explanations, world-building & area descriptions, graphics & visual style guides, audio & music direction, specific sound effect requirements, and dialogue style.

- When to use it: For art teams, narrative designers, sound engineers, and writers to establish a cohesive aesthetic and narrative experience.

- Impact: Ensures that the game's presentation consistently supports its core themes and emotional beats.

4. The Inner Workings: Mechanics & Feature GDD

This document gets down to the nitty-gritty of how the game actually plays. It’s for the designers and engineers who need to understand the systems at a granular level. - What it includes: The core gameplay loop (what players do repeatedly), detailed control schemes, player abilities & progression, enemy types & AI behaviors, weapon systems, item inventories, core game systems (crafting, combat, economy), UI & HUD specifications.

- When to use it: For system designers, programmers, QA testers, and level designers to build and refine the playable aspects of the game.

- Value: Prevents ambiguity in implementation and provides a clear reference for how game elements interact.

Staging Your GDD: A Grow-as-You-Go Approach

Building a full, comprehensive GDD from day one can be overwhelming and lead to quickly outdated information. A more efficient approach is to stage its development:

- Start with a one-page document: Focus purely on the high-level concept. Get consensus on this before expanding.

- Transition to a ten-page document: As the game takes shape through prototypes or early development, expand to include core mechanics, basic story beats, and target audience details.

- Finally, create a full GDD: Once the core vision is validated and production is underway, flesh out all content and detail. This iterative process ensures your GDD remains relevant and adaptable.

Beyond the Document: Modern GDD Formats

The "GDD" doesn't have to be a static Word document. Modern teams leverage various tools:

- Written Documents (e.g., Google Docs, Word): Still useful for centralizing information, though large projects can become unwieldy.

- Game Design Wikis (e.g., Confluence, MediaWiki): Online databases ideal for managing vast amounts of categorized information (items, characters, lore) and easy to update. Can sometimes obscure overall relationships.

- Collaborative Design Tools (e.g., Notion, Trello, Milanote): Offer flexible structures, visual organization, and integrated task management, fostering real-time team communication.

- Visual GDDs (e.g., Mural, Miro, or even physical whiteboards): Emphasize diagrams, flowcharts, and concept art to communicate ideas quickly and effectively.

No matter the format, the goal is clarity and accessibility. The GDD, in whatever form, is a living artifact of your game's evolving design.

The Story Heartbeat: Crafting Your Game Plot Summary

Beyond the mechanics and features, every compelling game has a narrative spine. A Game Plot Summary (also known as a synopsis or narrative outline) is a prose recounting of your game’s story, focusing on major events and character beats, emphasizing storytelling over technical minutiae. This isn’t a sales pitch; it's a deep dive for your internal team to understand the journey players will undertake.

A strong plot summary, created early in development, allows everyone on the team—from system designers to artists to audio engineers—to grasp the narrative arc. It helps identify potential storytelling issues, uncovers opportunities for artistic expression, and ensures narrative consistency across all disciplines. Think of it as the foundational script that guides the entire creative process. For an example of how compelling narratives elevate the player experience, you might read our Sonic X Shadow Generations review and consider how its story beats contribute to the overall enjoyment.

Why Your Dev Team Needs a Player-Focused Plot Summary

This particular type of plot summary is unique because its primary audience is your development team. It’s not a marketing blurb designed to sell the concept, nor is it a hyper-detailed critical path document. It's meant to foster internal understanding and alignment.

- System Designers can spot where gameplay systems might conflict with story beats.

- Artists can visualize key scenes and character transformations.

- Engineers can anticipate technical challenges related to narrative events.

- Writers can ensure consistency and identify areas needing further detail or exposition.

Key Principles for an Engaging and Effective Plot Summary

Crafting a plot summary requires more than just listing events. It requires strategic thinking about your audience (your team) and the medium (an interactive game).

1. Keep it Engaging:

Treat your plot summary like a short story itself. It should be readable, enjoyable, and intriguing. If it's a chore to read, your team won't absorb its crucial details. Use evocative language, build a sense of anticipation, and make your team want to see this story come to life.

2. Player-Focused Point of View (POV):

This is perhaps the most critical principle. Write the summary from the player's perspective. What does the player know? What do they experience? Avoid including information the player wouldn't know in-game (e.g., a villain's secret motive they discover much later). This helps you:

- Reflect the actual game narrative experience.

- Identify areas where player agency might be lacking.

- Ensure critical information is conveyed to the player at the right time.

- Clarification: If you need to include supplementary background information (like deep lore or character backstories), label it clearly as "Developer Notes" or "Background Context" separate from the main narrative flow.

3. Standalone Functionality:

Your plot summary must work as a complete story on its own. It should provide a minimal framework that can be critiqued, understood, and used for planning without relying on a "final draft" to resolve basic logic or setup issues. It should have a clear beginning, middle, and end, even if those are broad strokes.

4. Account for Gameplay Restrictions:

Game design isn't just about pure narrative; it's about interactive narrative. Your plot summary needs to integrate established game design constraints. - Are you making an open-world game? The narrative needs to allow for player freedom.

- Are there cutscene limitations? The story should primarily unfold through gameplay.

- Use the summary to catch and correct potential conflicts between story and mechanics early on.

5. Imply, Don't Depend on Gameplay:

While respecting gameplay constraints, avoid getting bogged down in highly specific or potentially changing mechanics within the core narrative. Suggest gameplay style and ultimate goals, but don't hardwire the story to a specific combat system that might evolve. - Example: Instead of "The player uses their triple-jump ability to clear the chasm," write "The player navigates a perilous chasm, using their athletic prowess to overcome obstacles."

- Use comments or separate sections for specific gameplay suggestions if they're crucial for context but not part of the core story.

6. Imply Budget:

Narrative choices have direct budgetary implications. Your summary should clearly indicate expensive requirements. - Example: A scene requiring "a massive battle with hundreds of NPCs" should immediately flag as a high-budget moment.

- Use comments to highlight areas of potential concern and suggest alternatives if the original vision proves too costly. This enables early discussions and avoids late-stage rework.

7. Don't Get Attached:

View your plot summary as a blueprint, not a sacred text. It's a tool for planning and communication, not the final piece of content. Be open to critique, and be willing to reshape the narrative to improve the overall game. The best stories often emerge from iterative refinement. Get feedback, revise, secure sign-off from key stakeholders, and then proceed to scriptwriting or detailed quest design.

Weaving Them Together: GDD and Plot Summary in Harmony

While distinct, the GDD and Plot Summary are two sides of the same coin: defining your game. They aren't meant to be created in a vacuum but rather to inform and complement each other.

- The GDD's Design & Style section will house the world lore, character descriptions, and overall narrative style that the Plot Summary brings to life.

- The GDD's Mechanics & Features section will detail the systems that the Plot Summary implies will be used to resolve conflicts or progress the story.

- The GDD's One-Page overview will often include a "Basic Story" element, which is the ultra-condensed version of your Plot Summary.

Think of it this way: your GDD provides the structural framework and the functional components of your game. Your Plot Summary injects the emotional heart and journey, ensuring that framework is compelling for the player. They work in tandem to create a holistic vision for your game.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid When Defining Your Game's Core

Even with the best intentions, it's easy to stumble. Being aware of these common missteps can save you significant trouble.

- Vagueness is the Enemy: "It's an RPG where you save the world." This tells no one anything actionable. Be specific about how you save the world, what kind of RPG, and why this world is unique.

- Over-Scoping from the Start: Dreaming big is good, but trying to fit every single cool idea into your initial overview or premise can lead to an unmanageable project. Start small, define the core, and allow for expansion later.

- Ignoring Audience & Platform: A mobile game's premise will differ greatly from a PC MMORPG. Tailor your overview to your target players and the technical realities of your chosen platform.

- Lack of Iteration: Thinking your first draft is perfect is a recipe for disaster. Embrace feedback, revise, and refine your overview and premise constantly as your game evolves.

- Getting Too Attached Too Early: This goes back to "Don't Get Attached" for plot summaries. Your initial concept is a hypothesis. Be prepared to challenge and change it based on prototypes, playtesting, and team input.

- Mixing Audiences in One Document: Trying to create one document that serves investors, artists, and engineers will likely serve none of them well. Create tailored versions as needed.

Practical Steps to Draft Your Own Game Overview & Premise

Ready to put pen to paper (or fingers to keyboard)? Here’s a clear path to follow:

- Define Your Purpose & Audience: Before you write a single word, ask: Who is this for? What do I need them to understand or do after reading this? (e.g., Convince an investor? Align my art team? Remind myself of the core vision?)

- Brainstorm Your Core Concept (The Elevator Pitch):

- What's the absolute essence of your game?

- What genre is it?

- What makes it unique?

- Who is the player, and what do they do?

- Example: "A post-apocalyptic crafting survival game where players must rebuild society by terraforming a hostile alien planet, alone or with friends."

- Choose Your GDD Starting Point: For internal development, begin with a one-page GDD. Get the core concept, design pillars, and target audience down. If you need to pitch, then structure a marketing/pitch GDD.

- Draft Your Game Plot Summary (Player POV First):

- Outline the major story beats from the player's perspective.

- What's the inciting incident? What's the main conflict? What's the goal?

- Keep it engaging and standalone.

- Identify potential gameplay hooks and budget implications (using comments/notes).

- Iterate and Get Feedback: Share your initial documents with trusted peers or early team members. Ask targeted questions: Is it clear? Is it exciting? Does it make sense from a gameplay perspective? Be open to constructive criticism.

- Expand as Needed: Once your core overview and plot summary are solid, gradually expand your GDD to include more detailed sections (mechanics, art style, audio) as your project progresses.

Moving Forward: From Premise to Playable Reality

Crafting a robust Game Overview & Premise isn't just about theory; it's the critical first step in bringing your vision to life. It’s the constant communication tool that keeps your project grounded, aligned, and exciting. By investing the time to clearly articulate what your game is, who it's for, and how its story unfolds, you’re not just documenting; you’re building a shared dream.

So, take that brilliant idea from your head, refine it through these frameworks, and give your game the strongest possible foundation. The journey from concept to finished product is long, but with a clear overview and premise, you’ll navigate it with confidence and clarity, creating a game that truly resonates with players.